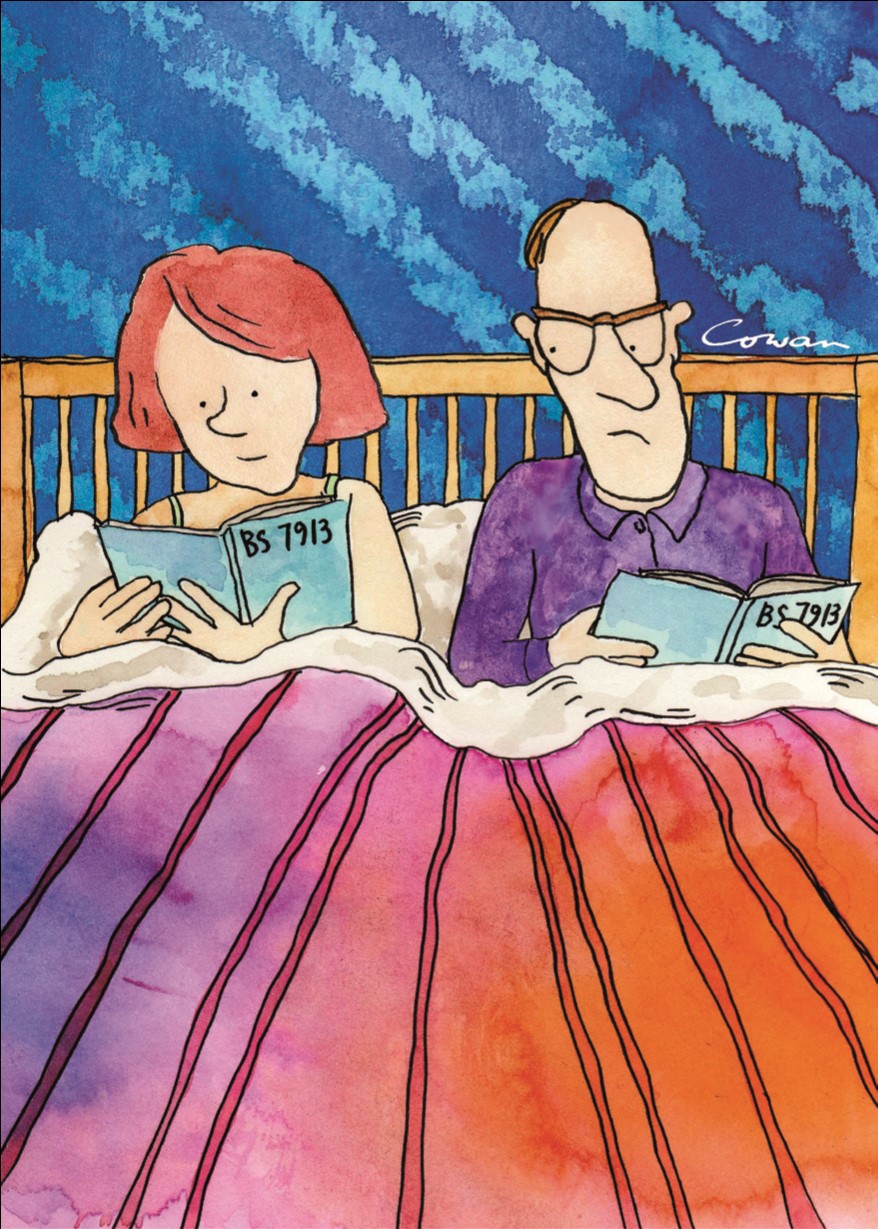

BS 7913

This article originally appeared as ‘Why building conservation needs BS 7913’ in Context 141, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in September 2015. It was written by John Edwards.

BS 7913: Guide to the Conservation of Historic Buildings, written by experts representing a range of professional and heritage organisations, is the only UK-wide standard of its type.

[Image: Somerset House, London: heritage impact assessments have been carried out for temporary installations, following BS 7913.]

British Standards are well known within all sectors but perhaps not seen as very relevant to the heritage sector. They can be seen as potentially damaging where they may impose modern thinking and standards which might be inappropriate. There are, however, numerous British and European standards that lay down best practice within the heritage sector, and the one that should have the most positive impact is BS 7913: Guide to the Conservation of Historic Buildings, which was published on 31 December 2013.

Unlike any other ‘guide’, this was produced by a broad range of experts from all professions, representing some of the most respected professional and heritage organisations from across the UK, including the IHBC. It went through an extensive public consultation process, which makes it the most authoritative UK-wide guidance on building conservation.

As a guide it touches on all essential issues, providing an excellent checklist of the things that should be considered. While building conservation experts who have a broad scope of knowledge should already have this, one must bear in mind that the majority of people who deal with historic and traditional buildings are not experts, and come from the mainstream property and construction industry. They typically will not refer to, say, the English Heritage ‘Principles of Conservation’, because they probably do not even know they exist. But they will have heard about British Standards and will hopefully follow BS 7913: 2013. This means that they will get to understand conservation philosophy, including ‘significance’ and how it is used. They will be directed away from some of the common practices that are unnecessary and damaging, such as solid-wall insulation and cement renders and, we hope, be encouraged to think about the causes of problems like damp, and not automatically install chemical damp-proof courses and such like, when they are rarely required.

During the consultation process there was a little criticism about the simple, straightforward language used in the standard, which is unlike many heritage ‘policy’ documents. This is one piece of advice that the drafting panel considered and rejected, as the document was intended to communicate with everyone involved with traditional and historic buildings. That meant using the most appropriate language for this very broad audience. Those involved in controlling and regulating conservation can therefore refer building owners, consultants and contractors to BS 7913 with the knowledge that it is easy to read and contains good, authoritative advice of the kind that they will not see anywhere else in one place.

If a mortgage valuation survey report insists that a chemical damp-proof course is required, sections [IP address hidden] and 6.10.1 can be referred to. They make an authoritative argument to ensure that the cause of any dampness problem is properly dealt with. This is reinforced by section 6.3, on the need to assess a building’s performance and on the need for building pathology.

Where building regulations deem it necessary for solid-wall insulation to be installed on traditional buildings following improvements, the same sections can be used to illustrate that this could be very damaging and therefore not ‘technically feasible’. More emphatically, in section 5.3.1 the document states: ‘Some energy efficient measures can have an adverse effect on sustainability.’

Where building owners or their consultants want to retrofit a building, section 5.3.1 sets out what should be the first consideration in making a building energy efficient and sustainable before installing retrofit ‘measures’. It reinforces the case for good building maintenance and repair, highlighting that this is a means to minimise heat loss. It states: ‘Elements such as walls can be over a third less energy efficient if damp.’

Where damp is concerned, maintenance and repair have to be of the appropriate quality. Keeping walls dry will often mean repointing mortar joints to the correct quality standards. Section 6.10.4 contains advice on repointing. Section 8.2 contains advice on supervision and quality management. This provides authoritative guidance, a standard to adhere to and a tool to control others in undertaking such work.

Building maintenance, which comes under section 7, is cited as the most important and common activity. Other sections also help to put over the need for good and appropriate maintenance and repair. For example: the purpose of repair (6.4), minimum work (6.5), investigation (6.6), proven techniques (6.7) and honest repairs (6.8).

While building maintenance is very important, organisations that have only a few historic buildings in their portfolio do not always differentiate between these and other buildings. BS 7913 tackles this by focusing on the whole maintenance management process from strategy to implementation. Normally building maintenance practice means demanding a minimum time on site, standardised components and, very often, using multi-skilled trades people working to standardised specifications. BS 7913 highlights the need for a different approach. The most appropriate expertise should be used and there should be sufficient time to execute the work properly. And, as cited in section 7.4: ‘Materials selected should be of appropriate quality, suitable for the intended use and sourced for the particular historic building to achieve best performance match as well as best aesthetic match.’ This section emphasises caution: ‘The removal of historic fabric and patina should be avoided as far as possible to retain authenticity.’

Significance is heavily featured throughout the standard. Analysis of significance is described in plain language. The document explains how to assess significance in group and individual values, and provides an excellent checklist of issues that should be considered (sections 4.1 – 4.4). It describes how significance is used from strategic levels down to the minutiae of operations in daily care. Both reactive and proactive methods of managing significance are covered. This includes the development and use of conservation management plans and the undertaking of heritage impact assessments. For those in the mainstream, this may be the first introduction to such issues. Even for many expert practitioners who are not totally familiar with management of significance, the basic descriptions provide a good first step into what is becoming the mainstay of conservation best practice in the UK.

The other issue that is repeated time and time again is competence in all areas of activity, even where building maintenance is concerned. ‘Those directing the works should have an understanding of the significance of the historic building’ (section 7.1). The document lists all conservation accreditation schemes and membership of the IHBC as a means of demonstrating competence.

One more very important point is made which can help rebut the imposition of other unsuitable British Standards is cited in section 0.1. ‘British Standards that are applicable to newer buildings might be inappropriate.’

The standard encompasses many other areas in addition to those discussed above. One of its main attributes is that it covers so much in one document. This includes the conservation essentials of significance and technicalities. It highlights implementation in best practice fashion, whether you are inspecting a building, developing and managing a project, or maintaining and repairing – or trying to get others to do all these properly. There are a number of courses on BS 7913. Elements of BS 7913 and further details can be found at www.environmentstudycentre.org.

John Edwards, lead author of BS 7913: 2013, is a director of Edwards Hart, historic building consultants.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.

Comments