The New Tenement: residences in the inner city since 1970

The New Tenement: residences in the inner city since 1970, Florian Urban, Routledge, 2018, 310 pages, fully illustrated, hardback.

Florian Urban is professor of architectural history and urban studies at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art. For almost all his adult life he has lived in inner-city tenement flats, ‘new or (mostly) old’. Admiring this building type for its flexibility and the successful urbanism that he sees it as supporting, he has written ‘The New Tenement’ to explain its place in the revival of urban development in inner cities over the past 50 years.

Urban defines ‘tenements proper’ as ‘four-to-seven-storey walk-ups on the block perimeter with ornamented facades, and often with shops and offices on the ground floor – buildings that are typologically similar to historic tenements in Berlin or Copenhagen or to turn-of-the-century mansion blocks in London or Paris’. He extends his survey to include ‘other dense urban residences that were built since the 1970s to enliven the city centres: medium-rise blocks with a setback from the street, three-storey terraced townhouses, [and] three-to-four-storey “urban villas”.’

This thoughtful and thoroughly researched piece of urban and architectural history focuses mainly on five extensive case studies: Berlin, Copenhagen, Glasgow, Rotterdam and Vienna. Urban is struck by the lack of local variation in the tenements’ architectural style. ‘The bulk of residential construction, it seems, reflects the global availability of the same design models, ideas, technologies and materials,’ he writes. ‘The most discernible local specificities in new tenement design resulted not from architects’ commitment to a regionalist agenda but from legal provisions.’

This perhaps understates the concern for context that Urban so well describes elsewhere in the book. In Glasgow, for example, this involved reinventing the city’s traditional tenements in new forms. Urban does not discuss the question of why, unlike other parts of the UK, there was historically such a strong tradition of tenement-building in Scotland. That is fair enough: in view of how common tenements are outside the UK, it is the relative lack of them in England that needs explanation.

Beyond the buildings themselves, Urban sees the new tenements as part of a movement in urban planning that rejected the functionalist, heritage-destroying, car-oriented approach of the 1950s and 60s in favour of protecting the rights of cyclists and pedestrians; reclaiming streets and squares for communication, leisure and play; and promoting relatively high densities and mixed use.

Often though, Urban recognises, the new tenements have benefited members of the middle classes like himself, rather than the original inhabitants of the inner city. That is not the fault of the building type, he suggests, but a consequence of the political contexts in which the planning decisions were made.

For the urban lexicographer, the book introduces some delightful terms that urbanists have come up with in describing the processes of renewal. They include the Dutch gebundelde decontratie (bundled deconcentration); the Danish byfornyelse (city renewal); the German behutsame Stadterneuerung (careful city renewal); and, from Austria, sanfte Stadterneuerung (gentle city renewal). A ‘fruit-salad estate’ is a housing development ‘comprising buildings of diverse outlines and heights’.

But Urban is surely wrong in defining the German Emmentaler- Fassade (Swiss-cheese facade) as one in which ‘repetitive windows in an unadorned plaster facade are lined up like holes in a Swiss cheese’ with ‘rectangular facade elements and repetitive windows’. The holes in the Emmental in my fridge look as reassuringly random in size and distribution as ever. New Tenements is well illustrated by more than 300 colour photographs and a particularly good selection of plans.

This article originally appeared as ‘Living in the city’ in IHBC's Context 160 (Page 50), published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in July 2019. It was written by Rob Cowan, editor of Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles

IHBC NewsBlog

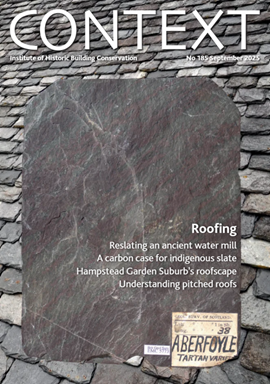

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

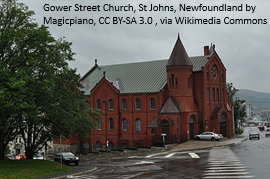

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.