KLH Sustainability reflect on the end of the zero carbon homes standard

Abby Crisostomo from KLH Sustainability reflects on the end of the zero carbon homes standard.

The end of Zero carbon homes means more than the loss of sustainable housing. Over the last decade the UK government, local governments and private sector industries connected to development have been working toward common definitions, workable requirements, innovative products and new processes to make "zero carbon homes by 2016" a reality. This month, those efforts were tossed aside under the guise of easing regulatory burdens to speed up the construction of new homes.

George Osborn's Productivity Plan, Fixing the foundations: Creating a more prosperous nation, promotes the decarbonisation of the UK’s energy sector, yet states:

"The government does not intend to proceed with the zero carbon Allowable Solutions carbon offsetting scheme, or the proposed 2016 increase in on-site energy efficiency standards, but will keep energy efficiency standards under review, recognising that existing measures to increase energy efficiency of new buildings should be allowed time to become established" (p. 46).

This disappointing decision has very real long and short-term consequences:

Money down the drain

Responsible builders have been preparing for the 2016 target for years, so backing down from it means a waste of not only effort on their part, but also money. As stated in an open letter response from more than 200 businesses, this type of abrupt change undermines “industry confidence in Government and will now curtail investment in British innovation and manufacturing.” Having no, or unclear, benchmarks means uncertainty, which means even more cost.

Squashing innovation

All of this uncertainty means confusion about what standards industry research should be working toward, which means fewer businesses are capable of investing in innovation. No standards also means no incentive to improve and no reward for delivering what used to be labelled as an achievement.

Pervasive fuel poverty

House building is not just about quantity, but also about quality. Standards like zero carbon are more than just feel-good sustainability add-ons. Energy inefficient housing may be cheaper for builders, but it ultimately pushes the cost to occupants who will have to pay more for power and heating. In the UK, 19.2% of the population lives in fuel poverty, the worst among 12 EU peer countries, and more than 31,000 deaths in the winter of 2012-13 have been at least partially attributed to fuel poverty and poor insulation. This was the stroke of genius in the previous ‘allowable solutions’ – it offered an opportunity for the UK to improve its existing stock as well as investing in new.

Favouring unsustainable housing

Lower standards for energy performance mean lower standards for homes overall. People do not want to spend more of their income on ever-increasing fuel costs, and savvy consumers have come to expect improvement in building technology over time, particularly in sustainability and health.

Threatening the UK’s ability to meet Climate Change Act obligations

Under the Climate Change Act 2008, the UK has a statutory target to reduce emissions by at least 80% from 1990 levels. Just last month, the Committee on Climate Change released a report on the UK’s progress and recommended actions, stating that to ensure that the UK continues to meet the long-term targets and complies with the requirement to show all new buildings are nearly zero-energy after 2020, the “zero carbon home standard must be implemented without further weakening.”

Increasing carbon emissions from buildings

The point of the zero carbon homes standard was to reduce carbon emissions from buildings and their contribution to the UK’s emissions. A Parliamentary environmental audit found that without significant measures, the contribution of the housing sector to the UK’s 2050 carbon emissions target could rise from 30% to 55%.

All of this erodes the UK’s position as a leader on regulation for, and products to meet, energy and carbon targets. The zero carbon home standard was far from perfect, but it was a defined, common goal for the industry to work towards. It was also a vehicle to showcase the UK’s leadership and innovation potential.

Not all is lost. The progress achieved so far and the learning that has been integrated into standard practice means that the momentum toward energy sustainability will not stop dead. Many clients are continuing to maintain strong standards, even in the face of the uncertainty, because they know that sustainability is about more than just standards, it’s part of the long game.

--KLH Sustainability 17:37, 30 July 2015 (BST)

Featured articles and news

Exchange for Change for UK deposit return scheme

The UK Deposit Management Organisation established to deliver Deposit Return Scheme unveils trading name.

A guide to integrating heat pumps

As the Future Homes Standard approaches Future Homes Hub publishes hints and tips for Architects and Architectural Technologists.

BSR as a standalone body; statements, key roles, context

Statements from key figures in key and changing roles.

ECA launches Welsh Election Manifesto

ECA calls on political parties 100 day milestone to the Senedd elections.

Resident engagement as the key to successful retrofits

Retrofit is about people, not just buildings, from early starts to beyond handover.

Plastic, recycling and its symbol

Student competition winning, M.C.Esher inspired Möbius strip design symbolising continuity within a finite entity.

Do you take the lead in a circular construction economy?

Help us develop and expand this wiki as a resource for academia and industry alike.

Warm Homes Plan Workforce Taskforce

Risks of undermining UK’s energy transition due to lack of electrotechnical industry representation, says ECA.

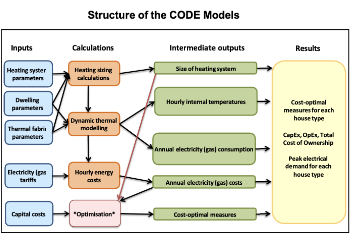

Cost Optimal Domestic Electrification CODE

Modelling retrofits only on costs that directly impact the consumer: upfront cost of equipment, energy costs and maintenance costs.

The Warm Homes Plan details released

What's new and what is not, with industry reactions.

Could AI and VR cause an increase the value of heritage?

The Orange book: 2026 Amendment 4 to BS 7671:2018

ECA welcomes IET and BSI content sign off.

How neural technologies could transform the design future

Enhancing legacy parametric engines, offering novel ways to explore solutions and generate geometry.

Key AI related terms to be aware of

With explanations from the UK government and other bodies.

From QS to further education teacher

Applying real world skills with the next generation.