Some impressions of management in the American construction industry 1957

This article presents the text of a speech to the Institute of Builders, by Peter Trench OBE, TD, BSc, MIOB. It was delivered at the Henry Jarvis Hall, RIBA, London on Wednesday 20 November 1957. H.S. Oddie FIOB President, was the Chair.

THE CHAIRMAN:

Ladies and Gentlemen, it is my pleasure to take the Chair at this the first lecture of our winter programme. I should like to say how heartened the Chairman of the Public Relations Committee and I are by the good attendance tonight. It is particularly nice to think that you are, in so doing, paying a compliment to one of our own members, to Mr Trench, who has so kindly consented to talk to us tonight. We have had many able and distinguished men to speak to us, and I am quite sure that no one will surpass Mr Trench in his ability and knowledge of his subject. I do not want to belittle his box office attraction, but he has asked me to say that he came here by way of a reserve - and what a reserve he is! It is typical of him, and I think of the spirit of the Institute, that when we found ourselves in a slight quandary Mr. Trench very kindly, and indeed nobly, stepped into the breach.

I have not personally had the pleasure of hearing him talk on this matter, but I have read with interest of occasions when he has spoken on other subjects, and my appetite is very much whetted! Mr. Trench, in common with the audience, I am looking forward to what you have to say to us.

Peter Trench needs no introduction to an audience of builders, and particularly builders in the metropolis, and therefore without further ado I call upon him to talk to you.

MR. TRENCH:

Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen, the title of this talk is: "Some Impressions of Management in the American Construction Industry." I am not really sure whether that should be "Some Impressions of Management.." or "on Management." But I thought it might be informative, although possibly not instructive, if I gave you, for some forty-five minutes or so, my impressions of the way that American management ticks. Now, in order to understand how American management ticks, I think it is necessary to get some idea of the background of management of industry in general and some idea of the American people - other than the one we already have from film, cartoons, Davy Crockett and all that sort of thing, and I think that one has also to get at the background of the American construction industry and then the background of American construction firm, and so I am going to work down them in that order.

My own visit was a one-man visit. I had been told they built fast, and I wanted to find out how it was they built fast. Nor could I understand with their high wages rates, how it was that they could get a building put up in what appeared, anyhow in theory, to be at a cost not greatly in excess of our own cost of building. Being a particularly idle type, and liking other people to do most of the work, I first took hold of the Productivity Team's Report and based my visit really on that. Not only did I go to the Secretary of the National Federation of Building Trades Employers for contacts, because he had been on the original Productivity Team, but in fact I even went to see some of the builders that the Team had seen when they were out there.

My journey was within the triangle formed by New York, Washington and Chicago, and that, of course although to me quite a long way, is really a very small part of the American Continent. And that, I think, is important, because it is very dangerous, after a short visit, or even after a number of short visits, to draw hasty conclusions. But I would say this again in my own defence, that I did have my ear fairly close to the ground, and I have a very personal interest in American matters in that my father is an American by birth. I do think that an attempt should be made to get this United States-British picture into perspective. I myself have been carrying on a somewhat pointed correspondence in The Financial Times with Sir Alfred Bossom, M.P. on the question of fast building in the United States, and I cannot help but feel that a lot of people, including possibly Sir Alfred Bossom, might have this business of comparing ourselves with the Americans on the wrong basis. If I can do anything to help get the thing into perspective tonight, then I feel I shall have done quite a good job.

I arrived on a Saturday. I went by ship; and going over, which took five days, I read again the report on the building of Fawley by the Foster Wheeler Company of the United States, and I couldn't help but feel at the end of that Report how amazingly good a public relations effort it was, but not a particularly good example of fine management. They appear at Fawley to have spent a very large number of millions of pounds in a very short time, and I felt like a lot of other people that - well I could have spent lots and lots of money in a very short time too if given the opportunity and it is no great virtue just to do that.

I cannot say that I went over there feeling particular(y) superior, but I thought that anyhow, from the cultural point of view, possibly, this country had something to show America, and thus I was determined not to suffer from any sort of inferiority complex. Those of you who have been to the States (and I am very sorry to see so many of you have!) will know what I mean when I say that to come into New York, with the setting sun behind the skyscrapers, is something which nobody can possibly forget. Despite all the facts and figures, the movies and everything else, the Manhattan skyline has to be seen to be believed. It has always struck me, coming home, what a rather unimpressive entrance to our own country we have got in Southampton Water. I got the impression, as soon as I landed in New York, that everything seemed so much bigger - their buildings, their cars, even Americans themselves, all seemed so much bigger somehow. It is a question of a sense of proportion, and you soon get used to it. But there is no doubt about it that, coming into the docks among all those skyscrapers you do feel that you are entering something pretty big - and exciting.

The next impression - and I am trying to build up a word picture - is the incredible traffic problem, with all those extraordinary coloured taxis and automobiles, which are nose to tail all along the New York streets. Well, they may have solved that problem since I was there - I do not know - but even London has nothing on some of the traffic jams they have out there! But it was when I found that they were selling the Sunday papers at six o'clock on Saturday evening that I realized I really had arrived!

Everyone was friendly. Somebody whom I had met only once before in my life was there to meet me, and I felt immediately that they were very interested in us as people, and that they were very interested and proud to show us round their own industry. They are a friendly and industrious lot. But it is a thing to be remembered, if any of you think of emigrating as a result of this lecture, that they are interested only in success. They are very ruthless with failure; the failure in the United States hides himself. Anything new is good until proved otherwise. I think you will agree that is almost the reverse of some of our philosophy over here, where everything new is no good until is has been proved to be good. But, on the other hand, I found that the nerve-racking noise, the pills and the stomach ulcers were all absolutely true. Many people would stop off for ten minutes or a quarter of an hour to take a glass of milk and a couple of pills. I do not quite know what for but, as far as I could gather, it was to take tranquillizers when they were het up and then other sorts of pills to get themselves het up again!

I was soon disillusioned sadly as far as my cultural superiority was concerned, because on the Monday evening I was invited to go to a Chinese art auction, and the very splendid American who asked me assumed I knew all about Chinese art and auctions. I had not been there for more than two minutes before he was pointing to some frightful-looking China horse and asking me whether I thought that was "Hang, Pong or Ting," and of course I hadn't a clue, but he not only knew the dynasty, but he knew how much it was going to fetch - and that is important, very important, because culture and economic costs all seem to merge very much with them.

I do not know if I have succeeded in giving my impressions of the people but I am now going to give you a few facts. I must say that figures are extremely difficult to come by, and in fact I still have not got the unemployment figures for the industry.

First of all, the organization of American employers in the Building Industry? there are some 400,000 firms - and I think that some of these figures, if you work them out, will surprise you. They employ 2,420,000 men. I think you will see from that, that, rather like ourselves the American building industry is not made up of a small number of large firms, but like ours it is made up in fact of a very large number of small firms, and they are organized into what is called the Associated General Contractors of America, Inc. They divide themselves into the Building Division, Heavy Construction, Railroad Contractors' Division, and the Highway Division. There is no differentiation between civil engineering and building. There are in addition to the A.G.C., the National Association of Home Builders, with whom I had nothing to do at all; I did not look at any house-building, nor did I visit the National Association of Home Builders, but they are a very big association and one that cannot be left out. Remember, too, as I talk there is very little federal control, that it is mainly State control, and that it is almost like moving from one country to another when you move from one State to another so far as conditions, miles and regulations and organization of the building industry are concerned.

Therefore there were just under two and a half million operatives made up as follows. There were 981,700 or just under a million employed by general contractors; there were 1,438,500, or just under l.5 million employed by special trades contractors. Those particular figures I think are interesting in that the special trades contractors outnumber the general contractors to a very large extent.

Coming now to the earnings of those operatives, the average hourly earnings of operatives employed by building contractors was 2.93 dollars - which is near enough £1 per hour. That is the average throughout the United States, averaging labourers and craftsmen. But in fact in New York the wage rate or earnings were 4.25 dollars per hour or thirty shillings per hour for bricklayers. Labourers in New York were paid the equivalent of 22s.6d. per hour, or 3.15 dollars per hour. Merely because I like the name, Omaha in Nebraska pays 3.42 dollars for its bricklayers as against 4.25 dollars in New York, and 2.10 dollars as against 3.15 dollars for its labourers. I merely bring that out because these rates vary very considerably from State to State.

The weekly earnings in the building industry in the United States average somewhere between about £30 and £35 a week. I know that everybody will say that of course it really does cost very much more to live there than it does here, and I agree with that, but I do not agree it costs anything like twice as much. Now remember, too, that there is no, or very, very little overtime and bonus. On the jobs I went on to - and I went on to some eighteen quite sizable contracts - I found no overtime or bonus. They average 36.4 hours a week and that again is an average throughout the United States. Normally it is an eight hour day and a five day week.

I must make mention here of the automobility of the average American operative, and that is something which one has to see to believe, because the very first thing that one has to do on site if one is a building contractor is to make a car park for one's operatives.

One last word on earnings. By comparison with other industries, I think I am right in saying that the construction industry in the United States is the highest hourly paid industry in the country.

Now something about the organization of these 2.5 million operatives. Unlike the national collective bargaining machinery in this country, in the United States not only does this collective bargaining operate separately in each locality and almost in each city, but a majority of the localities have separate bargaining for each craft or section of the industry, and I think it is really quite incredible that such negotiating machinery works at all. When you think of the painters in one city who are arguing about contracts for a year or two years and that the plasterers are arguing quite differently and entirely separately for theirs, and that between that city and the next the same argument is going on, it is quite incredible that they get to any sort of finality, but they do.

The philosophy of the trade unions I think is really very different from the philosophy of the trade unions in this country. When I visited Washington, I managed to get an introduction to Mr. Harry Bates, the President of the Bricklayers' Union. Mr. Bates, with his three vice-presidents, worked in a most wonderful suite of offices in Washington, all close-carpeted and full of secretaries, very difficult to get at, and a very busy and very important man. I do not know what his salary was, but I am quite sure it was very much higher than mine! Anyway, he had just come back from a six weeks vacation in Miami, and he was very pleased to talk to me about the American philosophy of labour. Whether he was pulling my leg or not, I leave you to decide, but he did tell me this. He was very interested in bricklayers, in profits and in negotiating machinery and during the course of the afternoon - I think this was really the highlight of my visit - he asked me to look out of the window and to look at the building at the other side of the street. This was another of those colossal things. He said, "Well, what do you see?" I said, "Well, it is a big tall building." He said, "Yes, I know but what is it clad in"; he spat the word clad; and I said "Aluminium." To which he replied, "Aluminium the ........s!" He went on to say, "But of course, if my boys work hard and fast it will be all right, but if not, these sheet metal fixers will take the bread out of our mouths." He also said, "We work hard and we work fast. We lay a lot of bricks and the building owner or the bricklaying sub-contractor makes money, "But", he said, "Once he makes more money, then we are going to ask for more." Well, that's fair enough.

That to my mind rather sums up the labour philosophy which I found. All the big jobs in the big cities are ticket jobs? if you have not got a ticket, you are out. In New York it costs you £50 to join some unions. When you come to think of it, if you are going to earn thirty shillings an hour, it is worth paying fifty quid to start.

Labour is recruited direct from the unions, and I cannot tell you about unemployment because I could not find figures for the building industry. I am quite sure, however, that there are pockets of unemployment and I am quite sure, too, that there is seasonal unemployment, and certainly unemployment between various big jobs, finishing and starting. There is a pool of labour in most of the big cities, and my own view for what it is worth is that productivity is well up on our own, for various reasons, and that individual output is anything from ten to fifteen or even twenty per cent higher than individual output in this country. I speak with some experience of that because I managed to get myself taken on as a bricklayers' labourer and I learnt quite a lot about productivity and tickets (because I had not got a ticket I eventually got slung out). But I was there long enough to find out how fast and how hard they worked. Therefore, I am not bothered about anybody saying, "They do not work as hard as we do." I say, without fear of contradiction, that they do. When I put this point of view to the American employer for whom I worked, he said, "Well, you should have seen these boys twenty years ago, then they worked." That was his reaction. But it looked as if they worked hard to me now, all the same ! His second reaction was to say, "If your boys don't work as hard as our boys, then your boys must be sitting on their arses!" They don't think much of their own productivity. In fact I have bought a copy of the American journal "Fortune" which discusses this very problem - this is just to get the thing into its proper perspective. The whole article is dealing with the productivity of various industries in the United States. The heading of this particular paragraph is: "Can builders ever be efficient?" This is what it says? "The least progressive of the industry groups we are examining is construction, which has probably been increasing its productivity at less than 1.5 per cent, a year. Exactly how much (or whether) construction productivity has been increasing is hard to say, for the figures are incomplete and unreliable. Some studies show practically no increase at all. The industry's backwardness lies both in the fact that much of the construction dollar goes into repair work (including painting and plumbing), whose efficiency is notoriously low, and in the fact that the industry is made up of thousands of small-scale operators who are ridden by restrictive practices, and handicapped by weather, building codes, and their own inertia."

Well, that is what an American magazine thinks of the industry. But I still think they work harder than we do!

The ready availability of material of course is one of the answers to why it is they can build fast - getting on the phone, asking for something, and having it within twenty-four hours, just made my mouth water! If one sub-contractor could not perform to your date, you just found another who could, and there always was another who could. It was a question of competition by service as well as by price, and I was extremely impressed by this sub-contractor service in construction in the United States.

Timber was both cheap and plentiful, and so was ready-mixed concrete, I did, however, take a note of some of the prices of materials and those of you who are buying materials in this country can compare those prices with what we are paying today. These are the May and June prices, I know you cannot generalise in things like paint, but this just happens to be Gloss External Finishing Paint, and it costs 35s. a gallon. Well, that is cheaper than we can buy Gloss External Finishing Paint here. Reinforcing Steel, £45 a ton, Sand 9/- a ton F.o.b. plant. Gravel, 10s.6d. a ton, f.o.b. plant. Common bricks - we have got them licked on this one - 215s. a thousand. Facing bricks vary, but the official statistics give the prices as 338s. a thousand. A 5 foot enamel bath,£19.15.6. (I think that is probably a little bit more expensive than ours); Vitreous china W.C. £8.12.3. Timber - very considerably cheaper, of course. If they pay about the same for materials, and sometimes a little bit more, it is a very interesting problem as to how it is that they can pay bricklayers thirty shillings an hour in New York and yet produce buildings at an overall cost of say only 50% to 100% more expensive than ours.

There are three methods of obtaining contracts - other than by a sub-machine gun, of course! - and I did not really see anything like that. There is first of all the lump sum bid contract, secondly there is the cost plus a fee contract and thirdly there is the joint venture. Now, I am going to skip over these rather quickly because I want to come to the organization of building firms. With regard to the lump sum bid, of course you all know that there are no such people as professional quantity surveyors in the United States. I did sit in at a bid meeting while they were discussing a lump sum bid, and I imagine that there were many similar meetings going on in this country at the same time, where similar sorts of conversations were taking place, such as, "How much do you think this will hold, Jim?" There was no apparent variation over a wider range of results than here, and I expected there would be. It was not unusual to have three-weeks to bid for a three million dollar project; ten days for a million dollar project. Remember, however, of course, that the main contractor does very little of the work himself, and I shall be coming on to that later. I noticed, too, that there was the odd contingency sum pushed in, and the sort of talk about "the man who went in at cost" and "the building owner who wanted to get the building at less than cost” all reminded me very much of home!

The percentage addition for overheads proper varied of course with the nature of the job. One builder reckoned to get one success in ten bids, but he had not had one in twenty consecutive bids. You must remember, of course, that in the main the American contractor only prices concrete, carpentry, brickwork and general conditions (preliminaries) and all the rest he leaves to the sub-contractor, but he does have complete control of the sub-contractors, and that is just one other reason for their fast building and good co-ordination - the absence of the nominated sub-contractor - though here I must except some of the big public buildings where you might get subcontracts let direct.

The fee contract interested me particularly, and I was told of Mark Eidlitz who had started a building firm - one of the most famous firms in New York - and who did all his work on a cost plus fee basis, and as far as I could make out people queued up to go to him because he was efficient, fast and honest. In fact, there are two concepts behind the fee contract - and there is an awful lot of fee contracting - and the first is reliability and integrity of the building company concerned, and its contribution to the planning of the project from the outset. The second was the speed of building, and the need to start and finish a revenue producing asset at the earliest possible moment.

In one respect my experience was not quite the same as that of one Productivity Team. In the case of a competitive lump sum bid for a public building, all the drawings are very complete before work starts - in fact, they are enormous in their quantity. But on many of the jobs that I went to have a look at, when I taxed the architect and the builder about this they were slightly whimsical in their attitude, saying, "Well, that's what we aim at." In fact, here I must tell a story about one particular contractor, building an enormous factory in a very short time, with thousands of men, for a big motor-car company near Detroit. This factory was only going to turn out the bumpers, so far as I could make out, for the cars! The thing was nearly finished when I went through the offices and there, in the midst of the acres of factory, I saw the most extra-ordinary activity, great machines ploughing up the earth, and all sorts of other things going on at the same time, and I turned to the engineer, and I said, "Good Lord, what's happening here?". He said, "Gee, they've decided to have a basement!" Well, they were certainly digging a big, big hole which they had not expected to dig when they started.

Under the fee system the cooperation between the builder and architect and the sequence of dates for information is very real, and when drawings arrive they are very numerous and very detailed. I am now coming to the core of my talk - I have taken a long time building up to it, but I wanted you to get the atmosphere of the thing.

First of all, I think I had better tell you that I "investigated", (if that is the right word, because it is very difficult to go in and say, "Show me your books,") five different American companies. I visited their head offices and the plant yards; I discussed matters with management and labour; and I think that I got a reasonable picture of their set-up. I took five quite different companies. The first based on New York was doing a 120,000,000 dollar turnover, say £40 million a year, doing all types of industrial and commercial work. The second had a turnover of about 40 million dollars in Washington, doing the same sort of work. The third was in Detroit, with a turnover of about 3.5 million dollars a year, building small shops, churches , etc. I then visited a 20 million dollars turnover company which did industrial but very little other building, I also visited a ten million dollar turnover company which did public utilities, including schools and the like, so I got a very good cross-section.

Two of these companies had their own head office buildings, the smallest one and the Washington one. The big one, with a 120 million dollar turnover a year, merely had a couple of floors in a gigantic office block in the middle of New York, and there did not appear to be any evident desire for a prestige building of their own, but this company did apparently consider very carefully in what big set of offices it would take its floor. In this particular one the gimmick was to have the lift girls' hair all dyed the same colour to match the lifts! Well, that's all right. But the impression that I want to give is that they thought it more important to be housed in a big office building with big prestige value because there were, say, a couple of big oil people or bankers in the same building, than to occupy a building of their own.

The Washington builder did, however, have a large converted house on the outskirts of the city, and the small man in Detroit had a very small office, which he had built himself, with all his plant in an adjacent plant yard - and he was the only one who had a plant yard anywhere near his office. One of the main and most important requirements seemed to be centralization and good communications for the staff, as well as good communications with customers architects and engineers.

The one thing which you will find in any American office is detailed documentation. These American builders believe in getting everything on paper - procedures, processes, rates and regulations, organization, job definition, company policy. Each company had a quite different organization and a quite different policy. Each also had a quite different set of documentation. I spent one complete afternoon in one of the smaller of such offices, just going through his documentation. Everybody had to fill in something before he did something else, and I said to him at the end of it all; " Do you have any difficulty with all these forms?" He said "No, but I get a lot of difficulty in getting anybody to take notice of them when they are filled in!" It surprised me that speed of action was not hampered by this form filling - but in fact it all served a purpose - to assist mental processes.

They have a much smaller head office staff than one with an equivalent turnover over here, and I should imagine you would find that in America the number of people in the head office of a builder would be about half the number of people in a builders' office here, doing the same amount of work and with about the same turnover. That is because they decentralize to their sites an enormous amount of work. They also treat their head office staff as inflexible but their site office as expendable - for instance, in bad times they got rid of site staff, but they will always hang on to their head office staff. There seems to be very little overlapping of staff. In fact, in the case of the Detroit builder I found that the telephone operator as soon as I came in pushed over a form for me to fill in saying whether I was applying for a job or whether I wanted to see somebody - and while she was doing that, not only was she acting as the telephone operator and receptionist but she was also stamping the post. All that in the case of a 3.5 million dollar turnover firm. I found, too, that many businesses were built around staff of optimum size, and by that I mean that they limited the number of contracts they took to the size of the staff. One firm I saw whose annual turnover was something like twenty million dollars was very slack, but they were

not particularly worried: they reckoned on getting a certain number of large contracts in due course and they were not interested in getting small contracts. They still kept their head office staff together, geared to their optimum turnover.

Now I come to top management in building firms. So far as I could make out the president over there combined the two offices that we know of chairman and managing director. Several vice-presidents would constitute the board of directors. A big New York company, however, had an executive vice-president, who took on the functions of the British managing director. I think that they were learning very fast that there is in a big firm a job for a chairman and a job for a managing director. In that company there were a number of vice-presidents who wore not members of the board it was really a reward for long service. For instance, when you had been chief buyer for twenty years, then I suppose you might become a vice-president, if you survived that long; though you might not be on the board of directors. The president of a big firm would consider that he had a dual function, one being an overriding control of the company's operations, the other obtaining business. And this matter of obtaining business was quite scientific in this big company that I visited. I saw on their organization chart a thing called "Contracts Department". When I saw that, I thought, "Hullo, now I know what they are talking about." But in fact it was not what I thought. It was in charge of an engineer, who was really a public relations officer, and it was part of his job to have absolutely up to date intelligence on matters such as what jobs were likely to come along, where they were coming from, and so on. It was also his job to get snippets about that particular company into journals and papers, to get it talked about, and to dine and wine "The Right People".

That particular company also advertised every month in this magazine "Fortune" from which I have already quoted - one whole page advertisement completely different every month. Their advertisement is aimed at the building owner.

Now, having assumed that the president has got the job, there comes the question of estimating, and here, of course, one found that the documentation differed with each company. Remember that there are no quantity surveyors, but the thing that struck me on the management side on estimating was the very great thoroughness and detail into which they went. I have here three different sheets each containing headings referring to what I suppose you might say was the estimating procedure of the fairly large Washington company to which I have referred. The first sheet is a fairly simple sort of thing, a sort of taking-off sheet showing quantities, who has checked it, and so on; they like to have a double check on everything they do when it comes to figures.

The second is the pricing sheet - this has three columns, equipment, materials and labour, and they in fact price their jobs under those three headings, each unit being priced, and again checked. Then there are four sheets of "General Conditions" - our preliminaries, which are priced separately. These cover every possible thing they could charge to the job. It is more of an aide-memoire than anything else, but I think it is not a bad idea. It starts with the project manager, and finishes up with a thing called "nuisance expense." I did not have the nerve to ask what that was, but I suppose if the building next door falls down, or if they make a lot of noise, and somebody sues them, then I suppose this is an allowance for that. They make allowances for a safety engineer, dormitories, tool sheds, carpenters' sheds, barricades, fences, electricity, heating and lighting, washing windows, pick-up trucks and utility trucks - in fact everything which could be made a charge on a job has been listed for pricing if required.

The smallest company, the one in Detroit, which had only fifteen head office staff for a 2.5 million dollar turnover, had four qualified engineers, and by that I mean people who had taken degrees in civil engineering - the president, two estimators and a "coordinator." As I say, they often use qualified men. Most general foremen or super-intendents are qualified engineers on the big jobs. The big American company I should think would have at least 25 per cent, of their staff made up of qualified engineers or graduates.

Let us now return to the small company. They based the whole of their business on their five estimators under a vice-president. These men estimate for work, supervise its carrying out, including buying and the placing of sub-contracts. The president himself visited each job once a week. This was at one extreme. At the other was the 120 million dollar turnover company, where there was a special estimating department and a sub-contractors' room. That was the room where the sub-contractors come, take off their quantities from the drawings made available and go out and price them. In some cases a sub-contractor would get a set of drawings, but in most cases he had to take them off in that room. Incidentally, one of the biggest companies in Now York sometimes sub-contracted all their work, and had on site a coordinating staff only.

Centralized planning other than by "Process Engineers" (more of whom later) I did not find. Whereas I think we are waking up to this question of short-term planning, I think they have been doing it automatically, but they have not made a fetish of it, nor have they got any special department dealing with it. It is of course all part of their costing policy.

Coming to the buying department of the building firm I visited in Washington, they dealt not only with materials but employed what they called expediters as chasers. In this company sub-contracts were handled by the Project Engineer in conjunction with the estimators. In New York, on the other hand, the large builder had combined material ordering, sub-contracting and expediting under his Purchasing Department, and those two schools of thought are worth thinking about. The emphasis being on the buying department on the one hand and on the contracts management department on the other. The big company had its emphasis on the buying department, and they not only placed orders for materials for sub-contracts, but they then chased them through on to the job itself. One of the New York builders had a separate and quite independent expediting department. That just expedited everybody and everything, and they really did chase from the time the contract was placed. They were concerned only with progress.

On the contracts management side I did not find such a tremendous difference from our own ideas on management in this country; it varied as between one company and the next but on the whole their procedures were all very similar to our own. They all had an elaborate system of programming and progressing work. I have got with me here the programme for the Loyola Seminary. This is a photostat copy of it. It looks very much like one of our own - though perhaps those at the back of the hall will not be able to see it. It has on the left hand side references to the various trades, sub-contractors, and across it are the dates and times for each of those trades or sub-trades.

It is a little bit fuller than most of ours. It gives the names of the subcontractors down the side as well as their time; it shows the figured time and the actual time and also something which some of us may not do viz: what they call "shop drawing programme". There are three horizontal lines therefore, one showing the programme time, the second showing the actual time it has taken to do this operation, the third line, which starts much in advance of all that, is the time for shop

drawings, when they want final detailed drawings. They put many details in the programme, including the number of cubic feet of the building. Then they have got a little block plan of the buildings showing numbered buildings relating to sub-contracts, and then down the right hand side they have got the main quantities with which they are concerned together with descriptions. For instance, they have got here 2,600 cubic yards of concrete, I78 tons of reinforcing steel, and so on, and all those little bits of information which tell a story. I think their programming is excellent.

Again, if I may be allowed the time to tell a story about bad programming, I was leaning over a barricade watching them digging quite a long way down in Detroit. They were digging the foundations for a departmental store. It was among a whole parade of shops and stores. As I looked a truck drew up behind. The driver looking at me said, "Are you anything to do with this?" And then he went on to say, "They are a bit behind schedule, aren't they?" I said "Are they?" "Yes," he said, "I should think they are. I've got a load of lingerie here for them!" Of course, he may have been at the wrong address, but that gives you some idea of the time they take!

Then there was a chap called a "process engineer", and he had a job which I really had not seen before or even heard about. His job was processing and vetting all drawings received from the architects, and also what they called their "shop drawings" from the subcontractors. His object in life was to ensure that all details of the working drawings required by the job were furnished in good time and in an unambiguous form in order to comply with the severe schedule of programming. He was the fellow who put himself into the mind of the site superintendent running the job on the site, and made sure everything was on the drawings before they went to site.

The fortnightly staff meetings was the main control they had from head office. They had fortnightly staff meetings of those concerned in most of these big companies for each contract, and also fortnightly site meetings which of course were for the subcontractors and other people concerned.

I consider that one of the biggest lessons for us is their cost management and accountancy. To say that the American Construction Industry is cost-conscious is an understatement - it is cost sub-conscious! Every firm had its own system of costing, some very much more elaborate than others, but they always had the same object, to show weekly, fortnightly or monthly, how much a particular operation was costing as compared with the target estimate. It was generally accepted that money was either made or lost on labour. They were not very interested in material. Most of them had an elaborate and comprehensive list of all possible labour operations on the site. This is typical of their documentation. For instance, one firm I visited had a formwork manual which went out to every site. If you wanted to know what timber to use, you looked at your manual and picked out the job you had to do, and there it told you how many bits of timber were required, and what size was needed etc., for that particular job. The same with this cost business. Everything was put down so that you could not forget it. They listed all the labour operations; that were standard. They were coded numerically, not for secrecy, but for ease of recording on the job at the end of each day. Then there was an additional check from the timekeeper, assuring the accuracy of the time allocations. He would go out periodically and find out where men were, he would note it in his book and cross-check with

the trades foremen on the allocation sheets to make sure that they were in fact recording them accurately. Now the point I want to make here - and this is only another impression but I think it is important - is this, that the trades foremen are very much more alive to the importance of recording statistical data than in this country.

The section leaders could be relied upon to allocate labour quite correctly they did not have to bother about fiddling bonuses; they did not have to bother either about whether a man was unloading something one minute and doing something else the next. The important point to remember is that on big jobs most men are specialists in the U.S.A. including even the chap who stands about in rubber boots and does nothing else but spread and level concrete.

The collation of all this statistical information so received was done either by a cost clerk on the site or by the timekeeper, or sent back and collated at head office, where the weekly cost statements are compared with targets. Short-term planning was automatically applied not quite the system of pro-measuring we are talking about here, but they did, of course look ahead, including targets, in order to see how much they were behind or in front of the target at the end of that time. But remember all the time the small quantity of work which the general contractor would carry out himself. Remember too, the almost universal use of ready-mixed concrete, which makes it a lot easier to cost concreting on site.

The last management impression that I would like to record is on plant management and mechanization. Here I was very surprised because I had expected when I visited what they call the plant yard to find everything highly efficiently organized, with masses of large machines all beautifully painted and numbered and all the rest of it. But I can tell you that, with one exception, their plant yards were more like junk yards. They seemed to be full of stuff, of reinforcing steel, odd bits of everything, and everything absolutely filthy. The only plant yard I saw which really had anything to compare with ours over here was at the big Now York builder's. Even he had the same policy as the rest of them, in that he just did not hold any plants he either bought it and sold it at the end of his job or just hired it. Now you must remember that this company had a turnover of 120 million dollars a year. I have a list of everything it had in its plant yard, and I think it is extraordinary that it has not got one large machine in its plant yard, not even a bulldozer, a scraper or anything like that at all - not a thing. On the other hand, it has got a lot of small power tools, and they all had a terrific amount of small tools. The plant depot was divided into non-mechanical plant, petrol, diesel and electrical plant, and it had good under-cover storage for a fitting shop. They use fork lift trucks in the yard for moving and stacking materials. There was no crane in the yard, and they were loading their own trucks up a timber ramp with a winch, which surprised me. Their plant organization consisted of a plant engineer, an accountant, a stenographer, a clerk, three foremen, nine fitter mechanics, one carpenter, and about ten labourers. This was the company with a 40 million pound turnover. In fact, I have got this from their balance sheet - though I think they are probably just as capable of foxing the public as any of our balance sheets are! The depreciated value of their plant as a percentage of turnover was 0.022 per cent.

One word on research before I end. I did not find any individual firm interested in carrying out its own research. The large company had a research engineer whose duty appeared to be keeping fully abreast of developments, including new materials. He was chairman of their research committee which met only four times a year to discuss and disseminate new methods and materials. He also had one other duty which I took note of, and that is that if on his way to work, he sees some other building going on and finds they were putting in a floor in five days instead of the usual six, then he would watch in order to find why they could do that particular operation a day quicker than his own firm. I thought that had something to it!

On overheads and profits, I found to my surprise that the net profit of these building companies was considerably lower than our own. The one whose balance sheet I examined only had a net profit after tax of 0.72 per cent. of turnover, and that is not a lot when you are dealing in several millions of pounds.

Now I would like to sum up my main impressions of management in the American building industry. The first was one of better education and training, that we were still behind not only in technical but in managerial training. I found a combination both of technical and managerial training was applied to many of the people entering building firms at all levels. For instance, a timekeeper would be studying at night school to become an engineer and also a manager. In time he would become either a site superintendent or he would go into the head office. There is a real demand for education - a real desire to improve.

My second main impression was one of incredible cost consciousness although they have not yet got round to costing cost-consciousness!

Thirdly, a sense of inquisitiveness and a willingness to try anything new. In fact, each of them was really a works study engineer in himself always making comparisons and always interested in machines and labour utilization figures and efficiency indices.

Fourthly, the relationship between architect and builder and also between inside and outside staff was very different from ours. There are no great social barriers there; there is no question of the white collar worker getting more than the outside man, they accept that each is necessary to the other.

Fifthly, I found there was no interdepartmental bloody-mindedness. It was all one effort of the whole firm, and if anybody called for help from another department, if that help was there, it was offered and it was accepted.

One last point. I think that their organizational fetish and thoroughness leads to some rigidity. We as an industry are much more flexible now than are the Americans, and I really believe we are catching them up in most things. I think we will pass them in management techniques within the next ten years. Now I do not want to stick my neck out, but they are becoming very rigid in their whole process of mental discipline. This, I believe to be a hand-down from certain European immigrants.

The last impression I brought away was the industrial pride of everybody in the building industry from the operative, the teaboy right up to the president of the company. They all felt a sense of importance, of being in this industry together. For instance, a carpenter was proud to be a carpenter and his girl-friend was proud too.

TIE CHAIRMAN: Mr. Trench has very kindly consented to answer a few questions.

QUESTIONER: One of Mr. Trench's great points was safety, but we have not heard about safety. As they have no external scaffolding in America, perhaps we could have a word about that.

MR. TRENCH: I have not brought in safety because I have dealt with that particular subject in other places, and I do not really want to gain the reputation of being a safety crank. I did, in fact, however, bring it in subtly, in that I mentioned the general conditions, in which they had a column and a space for safety engineers.

QUESTIONER: Is the attitude to safety very different from that in this country?

MR. TRENCH: It is really the reverse theory of this country, namely that it is fear rather than regulations which will make people safety-conscious. By that, I mean they do not have anything like the amount of regulations with which they have to comply in order to make themselves safe for work. They learn the hard way. They drop 150 ft. or so and don't bounce. But everybody on the big building sites would be wearing protective helmets, and they were not considered Sissies because they thought it was a jolly good thing to do - because, in fact, they might get hit on the head. I noticed on quite a number of the jobs that I visited a big board exhibited outside the yard, to this effect "This project has had 5,453,200 (or whatever it was) accident-free hours.” One big builder to whom I was talking in his plant yard had a first-aid caravan. I think I have told this story before, but he had a qualified nurse as well, and the site superintendent told me they had to hand pick this nurse to stop the boys going sick too often. The insurance man is a pretty important chap, and as far as I can make out if he came on to a building site of a firm which he was insuring, and he did not like the look of things, then he would smack a bit more on the premium. Money talks there. As to their accident record and accident rate, I cannot answer about that, but I can tell you that in their own rather curious way they are just as safety—conscious as we are.

QUESTIONER: I was wondering whether Mr. Trench could say a little bit more about the actual engagement of the operatives. I believe that is done through the Unions and not as we do it in this country.

MR. TRENCH: Yes, that is so. I do not know if it is the same in all States, but what they would do would be to ring up the local union and say "Send me up six carpenters." In that particular district they would say, "Send me up six finishing carpenters or formwork hands or first or second fixers," and if they did not get them they would send back to know the reason why. That made things fairly easy. On the other hand, there were of course times when they asked for more than six carpenters and they got two. But it was a very remarkable process, of merely ringing up the local union and asking for the men they wanted.

QUESTIONER: Could Mr. Trench say something about payment in relation to contracts?

MR. TRENCH: Payment as far as I could see - and again this may not be general of course - was done monthly. They had an accountant, on the big site, making out the monthly accounts which were passed on and they were pretty promptly paid. Again I am probably over-generalizing, but they seemed to be paid promptly, and in most cases they expected accounts to be paid within thirty days of completion of the contract. They had the equivalent of our variation orders, a change order with prices on it, and believe me they always had the price on it. It was based not on unit rates, but was based on what they could get. That is what cost a lot of money, because if you change your mind, and you have not got a basic price list, then you have to bargain for the amount. No job variation was carried out without a change order. They had a provisional change order in the first place in order to get on with it, and they then agreed the change order price with the architect. Of course, there are some people here who know much more about this than I do, and perhaps Mr. Wates would like to answer that one. As I say, I think they are paid monthly, and they try to get paid at the end of thirty days.

MR. WATES: Sir, we have a business in New York which we have been running for about twelve years. I would like to say this first of all, that in thanking Mr. Trench for his lecture I support everything he has said, though there is a good deal I should want to amplify. But I think he has given an extremely clear and splendid idea of the broad outline of American building management. Now, on this problem of how to get paid, everything is done in stages. There is no such thing as measuring, because, as American builders will say to you "You guys go round to measure building to see if it is the same as the plans. My God, I cannot understand it."

Now, I did make one or two notes which may be of interest, and I will confine myself now to one thing. Mr. Trench said that the American building operative was the highest paid in American industry. Well, I think that we ought to think about that very, very carefully, because those of us with pre-war experience in this country of building trades operatives will, I think agree they were about the lowest paid of all skilled craftsmen, and I think too, that perhaps for that reason we did not get the very best of the labour market. In America it is the exact opposite. The worker in the Ford Works might get 2.20 dollars an hour, but the bricklayer on the job would get 4.25 or even 4.50 dollars an hour, and for that reason I think the American building operative is the finest type of man that America produces. I leave it to you to decide whether you think that our own operatives (and I do not say a word against them) are as good, but, self-evidently, we do not get the best of the working population. With regard to superintendents well, I was engaging a superintendent once, and we were paying about 200 dollars a week, which is between £60 and £80 a week, for that man, and the chaps came in for the job would say, “Well, I worked this year on this or that", or "I worked for two years on that," and they had worked it may be for a dozen firms, and my first reaction was to say, "Why did you leave firm one to go to firm two," but I readily saw that such a question would be foolish because the answer you would get would be, "Well, do you want a guy with experience of only one firm, because that is really no experience at all?".

I only mention that as being illustrative of the American attitude towards this kind of thing that we are talking about.

QUESTIONER: One more question on the payment period.. What about retentions?.

MR. TRENCH: In am not altogether sure about that, but if I remember rightly on the jobs I asked about, that retention was ten per cent. on the first half of the contract and nothing on the second half.

QUESTIONER: In Canada, Sir, they are paid for the whole job thirty-one days after the architect says the job is O.K., and they trust the builder for one year to do maintenance. As I say, they trust him.

QUESTIONER: Could Mr. Trench say something more about industrial pride and is that reflected in the standard of workmanship?

MR. TRENCH: I personally do not think that the standard of workmanship in the States is as good as it is over here. Certainly, on the finishing trades, for instance, I was rather appalled at some of the things I saw. I do not know why it is, because one would think that with no bonus system it would be pretty good. Of course, it is very difficult to generalize, and I do not think I saw enough and I would hate to condemn all American builders. But I did get the impression that quality was slightly lower than ours on the job. On the whole, I think on painting and plastering, not that I saw a lot, the finished quality was not as good as it is in this country.

QUESTIONER: Can Mr. Trench tell us something about the forms of contract? Does the American contractor work on a fixed price for his job, and is he able to get from his supplying sub-contractors a fixed price for the work that they are going to do?

MR. TRENCH: The A.I.A. lump sum bid contract, which as far as I know has no variations, is a lump sum bid that is expected to allow for all contingencies and also to cover any fluctuation that he thinks might arise. On the other hand, he makes sure that the sub-contractors themselves and his suppliers of materials put in fixed prices themselves. The speed of course at which buildings go up every year lessens the risk of variations, but of course there is a constant increase in costs every year. I noticed that every builder there had his own sub contract form, although there was in fact the standard A.I.A. sub-contract form, and that is of interest. Now may I go off at a tangent on this question because it is something that particularly interested me. I think you have got to get this thing in perspective, because it is only on the big, tall city buildings that they have really got us licked in speed. But there are hundreds of smaller buildings there which do not go up any faster than we put them up. They seem to have a minimum of ten months for any sort of building, and a maximum of eighteen months, but they do not seem to be able to get it done in less than ten months. I looked particularly at a store on Park Avenue, which is very comparable to some of the buildings we are doing ourselves, and they were taking precisely the same time we were over here.

With these big, tall buildings you really can get a lick on. They have got very few frills, much of it being repetitive work in a big way, and the bigger the building, the more repetition there is, of course, and that is how they get a move on; that explains the speed. Beyond that, and I do not mind what anybody says, they are not fast on all typos of buildings. They are fast on big, tall buildings.

THE CHAIRMAN: One more question.

QUESTIONER I wonder, Sir, whether Mr. Trench could elaborate a little bit more on the question of the unions' attitude toward unemployment, restrictive practices, etc., as opposed to the attitude taken up in this country.

MR. TRENCH. Again I think they varied very considerably between the States. I will give you two examples, and it is amazing really when you think of this that they can get such a speed on. One is that in one State the maximum width of your paint brush is limited; in another State you have to employ a foreman for every three craftsmen, and if that does not happen, well, there is a strike. There was a strike on which lasted for forty eight hours when I was there - I do not know what they wanted or what they got - but there it was, there were plenty of these small strikes. As I have said, I am only trying to give impressions. I do not know the real answers. On the whole they seem to get round restrictive practices and still build pretty well.

THE CHAIRMAN: Gentlemen, I am sure you have given Mr. Trench a good innings, and it is now my pleasure to call upon Mr. Wykeham to express your thanks to Mr. Trench,

MR. WYKEHAM: Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen, it really is an enormous pleasure to thank Mr. Trench most heartily for his talk. My only regret is that Mr. Trench's time-consciousness - because I think that is what it must have been - has induced him to flip over all those pages so quickly, because I know there is a lot more he could have told us. Whether we could have absorbed it all is perhaps questionable. But it has been a most stimulating talk, and I am left with the feeling, which we have had given us before, that we have, after all, got an awful lot to learn from the Americans, though possibly they have still got a thing or two to learn from us. One thing that impressed me, as a member of the Institute of Builders, tremendously, was the way in which Mr. Trench traced the number of qualified men employed by American contractors of all sizes. Big firms over here no doubt employ a lot of qualified men but in the case of the smaller firms I am afraid the proportion is very small indeed, and if we are to have efficiency in building, I think that we have all got to think about this one very, very seriously at this Institute which has very largely got to produce the qualified men needed.

MR. Chairman, I am not going to make a speech. But I should like to say to Mr. Trench "Thank you very much indeed," on behalf of the Institute for this talk, I hope it is going to appear in print in the Journal, and that the whole membership of the Institute will be able to read it and absorb it. It has been most interesting - I would say almost exciting. Thank you very much indeed.

MR. TRENCH: Thank you, Sir, very much indeed for the nice things you have said, and I am glad somebody has enjoyed it! This is not really a paper of the kind or in the nature of what I am sure Sir Hugh Beaver will give you. I was just a stand-in, and, as I said, it was rather thrown together. I am sorry about the timing. Anyhow, next time I am asked by somebody else, I have still got one and a half hours' stuff left!

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description fron the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

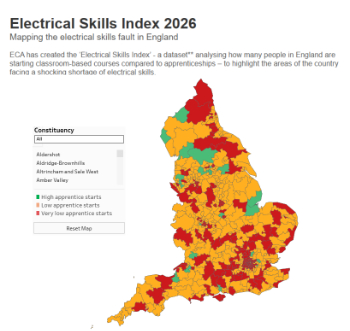

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.

Futurebuild and UK Construction Week London Unite

Creating the UK’s Built Environment Super Event and over 25 other key partnerships.

Welsh and Scottish 2026 elections

Manifestos for the built environment for upcoming same May day elections.

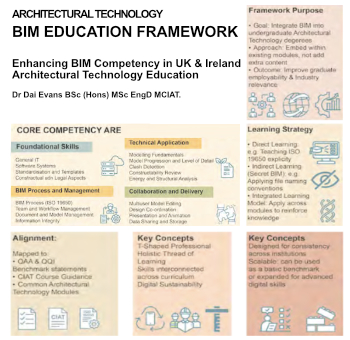

Advancing BIM education with a competency framework

“We don’t need people who can just draw in 3D. We need people who can think in data.”

Guidance notes to prepare for April ERA changes

From the Electrical Contractors' Association Employee Relations team.

Significant changes to be seen from the new ERA in 2026 and 2027, starting on 6 April 2026.

First aid in the modern workplace with St John Ambulance.

Solar panels, pitched roofs and risk of fire spread

60% increase in solar panel fires prompts tests and installation warnings.

Modernising heat networks with Heat interface unit

Why HIUs hold the key to efficiency upgrades.