Construction productivity 1977

Address given at the Institution of Civil Engineers by Peter Trench CBE Monday 21 November 1977.

There was a time not so very long ago when "productivity" was seen to be the key to our national economic performance. Those with a long enough memory will remember the rash of Productivity Team Reports (subsidised, I believe, by U.S. funds) shortly after the last war, including an excellent one from a team of experts from the Building Industry following a visit to the U.S.A. They will remember too the painful birth of incentive bonus schemes for building operatives which took place in the following years allegedly to increase productivity, although strangely at variance with U.S. practices so recently extolled. Then came the heady days of management consultancy and the introduction into construction of management techniques of varying complexity - critical path analysis, line of balance and the like. Some ten years ago the National Board for Prices and Incomes of which I was a member turned its attention to productivity in the Construction Industry and more recently it has been subjected to the spotlight of various committees and working parties of the National Economic Development Council. There are many names one could include in a roll of honour of those who during the last twenty-five years have examined us and found us wanting in the field of productivity - Emmerson, Banwell, et al..

It has been said that low productivity in this country stems from the low wage and salary structure (which) encourages over-manning and inefficiency, particularly in building. I was once a disciple of that philosophy, but now I have my doubts. The real truth I now believe is that despite the continuing but possibly temporary competitiveness of our exports abroad, inflation at home has become intolerable because earnings have risen faster than the increase in productivity. We have paid ourselves more than we have earned. We are no longer a low wage economy; we are a low productivity economy; we are a high unit cost economy. Higher productivity, i.e. increased value added in production per employee, is the only source of new wealth for the nation and therefore of higher living standards for us all. And it is here that any Government must face up to the dilemma, viz how to restrain prices and incomes but at the same time increase productivity. It is a dilemma, because the very fact of restraining incomes militates against increasing productivity. But to deal only with one side of the equation, i.e. that of incomes, is not going to solve the problem.

Indeed, productivity as a subject in the construction world seems to be out of fashion. Could it be that we have taken to heart the blandishments of our past mentors, pulled our socks up and are now beyond reproach? It would be agreeable - and popular with the industry - to think so, but ostrich-like.

In any event, to produce more building with less men is not a very popular concept when there are some 260,000 building workers reported on the streets. But is there not another way of looking at it? If we are able to build more building in less time with the same number of men, is it not a fact that the saving in cost to the nation in an era of inflation could speed the arrival of the day when we need those 260,000 men back in the industry? Or have I gone wrong somewhere? May be I have, in the twisted logic of those who would argue that in the non-revenue earning, or the revenue-subsidized public sector, the sooner we finish a building the sooner it becomes a drain on the nation's financial resources! But is not the better argument based on the concept of the extra cost to the nation of slow building in a time of double figure inflation. Reducing to single figures is obviously an achievement but of little use if we inflate twice as fast as our industrial competitors.

Let me refer to two quite separate and independent publications, both published last year. The first is "The Public Sector Housing Pipeline in London" produced by the London Housing Division of the Department of the Environment. It would seem that housing schemes in a sample of London boroughs took between four and nine years to complete. Some schemes took more than eleven years. It is suggested that if the construction period alone, averaging three years and four months, could be cut by 20% London would get 10,000 extra houses. Furthermore the GLC by cutting one month off the programme could reduce its capital borrowing by £1.9m saving £230,000 annually.

But probably more disturbing is the second publication, a survey carried out by Slough Estates entitled "Industrial Investment - a Case Study in Factory Building". This survey was carried out in August 1975 and covered the actual construction of a. factory of 50,000 sq. ft. with normal ancillary office buildings from conception to completion in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Belgium, the U.S. A., France and West Germany. The results were devastating and shame making for the United Kingdom. In every department of the game we appear to have been outgunned by the others - in some places by a mile. Take the production of architectural drawings as an example. The United Kingdom took twenty weeks against Canada's four, and the next worst after us was Australia with fourteen weeks required for a similar factory – nearly one-third less than the United Kingdom. It took twenty-six weeks to get all the necessary permits to develop in the United Kingdom, three in Australia, and our nearest rival was France with sixteen. We were one but bottom of the table in the time taken, for pricing, beating West Germany into last place, but took nearly four times as long as the fastest. Again in construction we took the booby prize, taking in fact nearly twice as long as West Germany, but more than twice as long as Canada, the U.S.A. and Australia to erect the building.

Ah! you will say, but what about the cost. And here is the rub, for adjusting the cost relationship with U. K., Belgium was the only country of the seven where the factory cost more.

Now I know all about the comparison argument and the unfairness of international figures, the rates of exchange, comparative outputs, environmental standards, narrowness of the sample and the like, but on the basis of the facts given in the survey one cannot escape the conclusion that there is, or was, something very wrong with the way we set about and carried out our building. I say "was" because It could be argued that in the United Kingdom the survey took place just before the present recession, during the last chaotic stage of overload. Even so, and here I admit entering the field of hypothesis, were the exercise to be repeated today I fear that it is unlikely that our performance would be such as to eliminate the gaps between us and our nearest international industrial, rivals. One paragraph of the report however should fill us all with very considerable alarm. It states "The conclusions to be drawn from the survey are simple and straightforward. British factory development and investment cannot compete with costs and delivery schedules of other countries. When British industry again expands, unless investment opportunities in the United Kingdom are competitive, investment will inevitably be diverted to countries where systems are more conducive to rapid achievement of investment aims and where risks are consequently less." That is not my observation, it is the observation of a powerful industrial organisation which is in a position to put into effect policies based on its own conclusions - unless they are rebutted.

However much one might disagree with the drastic implications of such a conclusion, there is little doubt that our industry and those who use it are only just beginning to grasp fully the impact of inflation on a project which is not built with maximum speed, indeed in the U. K. we are getting the worst of both world(s), for not only is our inflation rate higher than our competitors, but the construction process takes longer. It could, of course, be argued that all this is hog wash so long as the economic recession, together with a declining volume of building, persists in the U. K. if only on the psychological score that nobody wants to work themselves out of a job. That however is side-tracking the whole issue, namely the effect of efficient and speedy building on the economy as a whole in good times as well as bad. It has always been my contention, and still is, that the powers that be, particularly in the Treasury, have never made a serious "in-depth" study of the implications of a really productive construction industry on the economic health, let alone the social health, of the nation. If they had, I doubt whether we would be in the parlous state we are to-day. By the same token not enough thought has been given to speeding up the total building process; indeed where recommendations to this effect have been made over the last few years - vide Dobry, on whose committee I sat - in the main they have not been accepted.

I would ask those who would argue that fast building and high productivity are not synonymous to examine the ingredients of the former as defined in the second paragraph of this treatise. And to the purist who argues that it is the optimum and not the maximum speed which matters I would say that at the rate of inflation we have in this country the two more or less coincide!

One analysts of our problem in construction would suggest that the length of time taken in this country from the time a building project is conceived to the time it is completed stems partly from "the system”, partly from "an attitude of mind" and partly from incompetence. It is my belief that while the degree of competence, both technical and managerial, varies from country to country, we in the U. K. are not noticeably more incompetent than our international competitors. Of course there is a lack of consistency even in the best firm: there is also great scope for improvement of the average, but by and large I have found this to be the case with few exceptions (Sweden being one) in the construction industries of most other industrialized countries of Europe. Indeed I have evidence particularly in the U. S. A. that, given their conditions, U.K. management is as good as if not better than their own.

If I am right in this belief, then this particular analysis leaves us with "the system" and "an attitude of mind". These in fact are inter-related for "the system" has developed as a result of an attitude of mind and it will require a fundamental change in the attitude of mind to change the system. The great conundrum is how to bring such change about bearing in mind that it will probably require discarding long cherished principles and beliefs and the winkling out of large numbers of people who have vested interests in the status quo and the entrenched (and sometimes cosy) positions in which they find themselves to-day.

If one interferes with those factors basically at the root of that lengthy period prior to the start of a contract on the sites one is accused (IDCs) of tampering with the location of industry, etc., best suited to the country at a particular moment of time, or one is accused (planning procedures etc.) of tampering with and wrecking the environment, or (building regulations, etc.) even risking health and safety. There are a million-and-one reasons why something should not be done and a million-and-one people to make sure you do not do it. If one tries to cut down the time of architectural drawings, one is accused of interfering with the right of a building owner to change his mind, or the need for the Quantity Surveyor, and ultimately, the Builder for maximum information. If one questions the whole concept of the role of the Quantity Surveyor or the Bill of Quantities and links it with the average Builder's method of pricing one is accused of everything from treason to blasphemy. Whoever said "every new building is a new invention" (Gropius?) was right, but should have been wrong.

Some 20 years ago after working as a bricklayer's labourer for a very, very brief spell on a building site in New York during a visit to study productivity in the U. S. Construction Industry, I wrote an article in the Financial Times under the title "An Attitude of Mind". It produced quite a storm of dissension. I was accused, among other things, of not understanding the benefits of the natural conservatism to be found in the British temperament. I do - I really do - but I am not prepared to believe that we are so inflexible and so unadventurous and so obstinately of the belief that we are the only ones in step, that we would rather see our sacred cows join the gadarene swine than make a serious attempt to put our house in order. Putting our house in order must stem from an admission of shortcomings. To establish the shortcomings and come up with proposals could best be done by the Industry itself. Who will take the lead?

This is certainly the time to rethink. The Construction Industry could in fact change its public image by so doing, but what is more important, it could be in a position to make a contribution to the economy so much greater than hitherto that Governments and the Treasury would hesitate a little in future years before making decisions which would interfere with its effectiveness.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

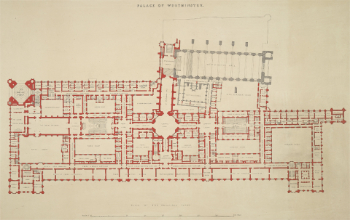

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

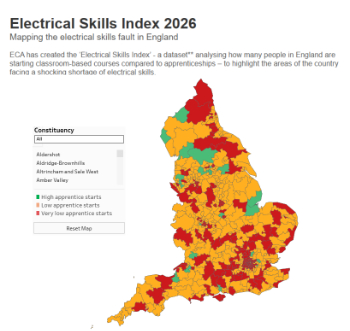

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.