Landownership in England in 1909

A national survey carried out as a basis for financing Lloyd George’s spending provides valuable information about historic places, as the results for Gloucestershire show.

|

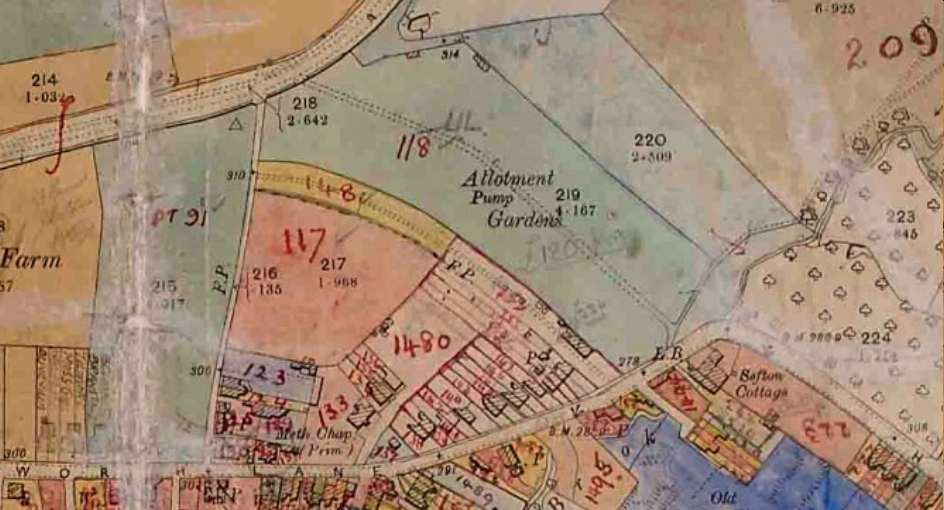

| Ordnance Survey map 26.12 (Gloucestershire Archives D2428/3 with thanks also to Marin Bailey) shows Ryeworth Field allotment gardens, hereditament number 118, 4.2 acres (1.7 ha), valued at £500, and owned by Charlton Kings Urban District Council. |

David Lloyd George, Liberal chancellor of the exchequer, introduced a budget in 1909 which caused a major constitutional crisis. He was looking for ways of raising more revenue – a not unusual situation – to fund the modest old-age pensions introduced in 1908 and a naval building programme. The rejection of the budget by the House of Lords gave him a campaign platform: ‘Peers v People’. Two elections in 1910 led to the Parliament Act 1911 restricting the legislative power of the House of Lords. But by this time the budget, in the Finance Act 1909/10, had been passed.

This debacle was caused by Lloyd George’s proposal to tax the ‘unearned increment of land’. He recognised that land increased in value not through the action of the owners, but because of potential building sites near expanding towns, and where coal or other minerals were mined. Lloyd George proposed that when land was bought, sold or inherited, any increase in value should be taxed, which required a baseline value to be established. The Inland Revenue conducted a national survey, in which each piece of land was valued as of 29 April 1909, even if an actual survey was not carried out for some years after this date.

The Poor Law Unions’ rating assessments in April 1909 were the basis of the survey. These lists were copied into large red books, called Domesday Books or Valuation Books, parish by parish in alphabetical order. The Inland Revenue grouped parishes into convenient units known as tax parishes, identified by the name of the first parish in each book. Entries were numbered in sequence, creating the hereditament numbers entered on Ordnance Survey maps to identify properties. Owners could require multiple properties to be assessed as one lot, or as individual lots. These records are in local archives offices, together with draft OS maps.

A surveyor’s visit followed; he went armed with a ‘field book’ in which Inland Revenue clerks had entered the basic details of each property as in the rating lists; observations about the property and valuations were recorded in them. The field books are in the National Archives. They are fascinating in their descriptions of houses, cottages, factories, mills, warehouses, churches, allotments and so on, but difficult to use in a large-scale enquiry within an area. Owners were informed of the valuations, and copies on Form 37s exist in local record offices. Owners had a short period in which to challenge the valuation. Most cooperated, but some brought cases in the courts against the Inland Revenue.

Inevitably there are imperfections in the clerical work and in subsequent record-keeping by the Inland Revenue. Some area offices were better than others. Oxfordshire has a remarkably ‘clean’ set of valuation books which the Archives Office has scanned. Bristol Archives appears to have a very full set of records. Gloucestershire has a mixed bag; they have been transcribed and are on a dedicated website supported by the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society: www.glos1909survey.org.uk.

The survey results can be interrogated in numerous ways. For example, footpaths or public rights of way can be examined, for which an allowance was made against the value of a property. More than 2,300 rights of way are recorded in the Gloucestershire records, the allowance being generally in the range £5 to £50. ‘There is a public footpath following the stream but not affecting the value to any material extent, say £5’ was the surveyor’s observation on a pasture in Bisley. However, the allowance for a right of way on a farm in Woodmancote in Bishop’s Cleeve was £125, for one on Charlton Kings Common £500, and in Ullenwood on Leckhampton Hill £400. The Recreation Ground in Gloucester, owned by Gloucester Corporation (9.25 acres, 3.7 ha) was valued at £960, for which the allowance was £960.

A surveyor’s description of a property can be exceptionally interesting. Chavenage House, for example, owned by G Lowsley-Williams, was described in the field book for Tetbury as ‘Freehold house, building, land & 2 cottages. House: stone & stone tile, part 400 years old & part 6 years. Very good.’ The new part was indeed new; a west wing had been built in 1904–5, begun by the architect JT Micklethwaite. But, as the surveyor noted, ‘the house has considerable historic interest & many of the bedrooms are named after distinguished persons who slept in them. Some are Oliver Cromwell’s room, Gen Ireton’s, Queen Anne’s, Sir Hugh Cholmondley’s, Harley’s, Col Stephenson’s, Sir Philip Sydney’s Room & Lord Essex Room.’ The owner during the Civil War was Colonel Nathaniel Stephens, and it is said that in 1648 Cromwell and Ireton visited Chavenage to persuade Stephens to sign the Bill of Impeachment of Charles I.

The former banqueting hall had an ‘antique carved oak screen, dated 1617’. The surveyor’s note here adds to the description of the screen in The Buildings of England: Gloucestershire, ‘mostly nineteenth century but presumably incorporates much old material’. The gardens and grounds were briefly described and the shrubs valued at £50. There were two motor garages, a coach house for four coaches and another for one, and good stables. ‘The house is heated nearly throughout with water radiators supplied from boiler in cellar & lighted by acetylene gas.’ Thirteen acres (5.2 ha) were valued with the house. The total was £9,450, of which the buildings were £8,500 and the site £750; the timber was valued at £150. Such an example helps to establish a scale of values.

A different type of enquiry can be illustrated from the survey of a parish on the northern border of Bristol, where development had started in the mid-19th century. Horfield ancient parish was in Gloucestershire but the manor was an endowment of the Bishopric of Bristol (created 1542). The southern part of the parish was made an ecclesiastical district of St Michael and All Angels, Bishopston; it was taken into the City of Bristol in 1897 and the rest of the parish in 1904. As a result, the 1909 records are held by Bristol Archives (except for the field books). To date, the details of 1,736 Horfield properties have been transcribed, some properties include several houses.

When James Monk became bishop of Gloucester and Bristol in 1836, he set about using the Horfield endowment to create a fund for churches in the Bristol area. In 1841 he sold a substantial landholding to Anthony Mervin Reeve Storey, later Story-Maskelyne, but housing development started with his son. In 1852 Monk promoted enfranchisement of the copyholders; their conversion to freeholders was a stimulus to building development. He set up a trust to manage the bishopric’s land. The Shadwell family, holding the lease of the manor, was another significant landholder; a family trust was created in 1777 to manage this property. The 1909 survey reveals that nearly half the houses were leased by one or other of the trusts. The Rev Henry Richards, the rector of the ancient Horfield parish church, was also a substantial landowner. Bishop Monk died in 1856. It was Bishop William Thomson who created the district of Bishopston as soon as St Michael and All Angels, built by Richards, was dedicated in 1862.

A small agricultural parish, 1,299 acres (525.7 ha) in 1901, Horfield’s population in 1801 was only 119. In the 1841 census there were 141 houses. The 1843 tithe map shows that a few houses had been built along the southern end of the Gloucester Road, which led from Bristol northwards and bisected the parish. By 1901 the population had increased to 13,975, by which time Gloucester Road was substantially built up; 529 houses were numbered, 258 being ‘house and shop’. Values ranged from £273 to £3,564, with the majority being over £500.

The survey shows the relative social standing of Horfield’s new houses. The two trusts and private owners were willing to sell land to builders, and nearly one in five houses was owner occupied. Egerton Road had been laid out quite soon after the copyholders’ enfranchisement, leading westward from the Gloucester road. It was bishopric land. By 1909, of 120 numbered properties, and one divided into two, 36 were owner-occupied. Valuations varied between £368 and £475, with a few smaller properties and one larger one, £975. Three-storey, semidetached houses survive in the road which led almost directly to the new Bishopston church. At the west end of the road was St Bonaventure’s Friary church, value £12,540.

The Horfield developments were occupied by a relatively affluent group of people as houses in Monk Road and Shadwell Road illustrate. The only poor neighbourhood was in Golden Hill; 42 houses had been numbered, and with two exceptions they were valued between £105 and £150. These were much more like the dense housing in south Gloucester. Georges and Co’s Bristol Brewery owned a house and an off-licence here, now the Gloucester Old Spot.

Sources

- The Buildings of England Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds, David Verey and Alan Brooks.

- Peter Malpass and William Evans (2020) ‘Bishop Monk and the Horfield Question: another view’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 138.

- www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10379544/cube/HOUSES

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 171, published in March 2022. It was written by Anthea Jones, who was head of history and director of studies at Cheltenham Ladies’ College. Now retired, she is the author of several books on Gloucestershire history, most recently Johannes Kip: the Gloucestershire engravings.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Membership Journal Context - Latest Issue on 'Hadrian's Wall' Published

The issue includes takes on the wall 'end-to-end' including 'the man who saved it'.

Heritage Building Retrofit Toolkit developed by City of London and Purcell

The toolkit is designed to provide clear and actionable guidance for owners, occupiers and caretakers of historic and listed buildings.

70 countries sign Declaration de Chaillot at Buildings & Climate Global Forum

The declaration is a foundational document enabling progress towards a ‘rapid, fair, and effective transition of the buildings sector’

Bookings open for IHBC Annual School 12-15 June 2024

Theme: Place and Building Care - Finance, Policy and People in Conservation Practice

Rare Sliding Canal Bridge in the UK gets a Major Update

A moveable rail bridge over the Stainforth and Keadby Canal in the Midlands in England has been completely overhauled.

'Restoration and Renewal: Developing the strategic case' Published

The House of Commons Library has published the research briefing, outlining the different options for the Palace of Westminster.

Brum’s Broad Street skyscraper plans approved with unusual rule for residents

A report by a council officer says that the development would provide for a mix of accommodation in a ‘high quality, secure environment...

English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023

Initial findings from the English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023 have been published.

Audit Wales research report: Sustainable development?

A new report from Audit Wales examines how Welsh Councils are supporting repurposing and regeneration of vacant properties and brownfield sites.

New Guidance Launched on ‘Understanding Special Historic Interest in Listing’

Historic England (HE) has published this guidance to help people better understand special historic interest, one of the two main criteria used to decide whether a building can be listed or not.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.